Your Request is under process, Please wait.

Your Request is under process, Please wait.

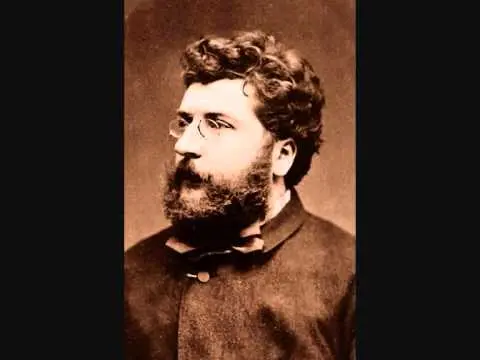

At its premiere in Paris in 1875, Georges Bizet’s opera Carmen was an absolute disaster. The respectable, middle-class audience of the Opéra-Comique was utterly scandalized. They had come expecting a polite and moralizing tale, but were instead confronted with a story of shocking realism, populated by smugglers, factory workers, and fortune-tellers. Most scandalous of all was its heroine: Carmen is not a virtuous maiden or a repentant sinner, but a fiercely independent, sexually liberated, and ultimately amoral woman who lives and dies entirely on her own terms. The opera’s gritty portrayal of lust, obsession, and brutal violence was simply too

...At its premiere in Paris in 1875, Georges Bizet’s opera Carmen was an absolute disaster. The respectable, middle-class audience of the Opéra-Comique was utterly scandalized. They had come expecting a polite and moralizing tale, but were instead confronted with a story of shocking realism, populated by smugglers, factory workers, and fortune-tellers. Most scandalous of all was its heroine: Carmen is not a virtuous maiden or a repentant sinner, but a fiercely independent, sexually liberated, and ultimately amoral woman who lives and dies entirely on her own terms. The opera’s gritty portrayal of lust, obsession, and brutal violence was simply too much for the public and the critics, who condemned it as immoral and vulgar. The failure was a devastating blow to Bizet, who died of a heart attack just three months later, convinced his masterwork was a flop. He would never know that his scandalous creation would, within a decade, conquer the world and become the most popular and frequently performed opera of all time, a timeless masterpiece of passion, obsession, and unforgettable music.

Quick Facts

Composer: Georges Bizet (1838-1875)

Title: Carmen

Genre: Opéra-comique

Librettists: Henri Meilhac and Ludovic Halévy, based on the novella by Prosper Mérimée.

Premiere: March 3, 1875, at the Opéra-Comique, Paris.

Period: Romantic

Famous Arias and Choruses: Prelude, "Habanera" (L'amour est un oiseau rebelle), "Seguidilla" (Près des remparts de Séville), "Toreador Song" (Votre toast, je peux vous le rendre), Flower Song (La fleur que tu m'avais jetée).

Average Performance Time: Approximately 2 hours and 45 minutes, including intermissions.

Gritty Realism and Exotic Color

The premiere of Georges Bizet's Carmen on March 3, 1875, stands as one of the most notorious fiascos in opera history. The Parisian audience, accustomed to the grand historical pageants and sentimental comedies that usually graced the stage, was horrified. They witnessed a stage populated not by noble heroes and virtuous heroines, but by working-class cigarette girls, army deserters, smugglers, and gypsies. They were confronted with a story that dealt frankly with sexual obsession, jealousy, and brutal violence, culminating in a murder on stage. And at its center was Carmen, a heroine so shockingly amoral, so fiercely independent, and so unapologetically sexual that she defied every convention of the 19th-century stage. The critics savaged the work as obscene and the premiere was a catastrophic failure. Bizet, already in poor health, was crushed by the rejection. He died exactly three months later at the age of 36, believing his greatest work was a worthless disaster. He would never live to see Carmen become a global phenomenon and the very definition of what a popular, successful opera could be.

From Opéra-Comique to Verismo

Part of what made Carmen so shocking was the venue for which it was written. The Opéra-Comique in Paris was a state-sponsored theater intended for "wholesome," family-friendly entertainment. Its productions were characterized by spoken dialogue alternating with the musical numbers (the original definition of opéra-comique). Bizet and his brilliant librettists, Henri Meilhac and Ludovic Halévy, took this traditional form and subverted it completely, injecting it with a dose of gritty, realistic drama that pointed the way toward the Italian verismo (realism) movement. They created a work of intense psychological drama and raw, violent passion that shattered the genteel conventions of the genre.

A Synopsis of the Drama

The story is set in Seville, Spain. In Act I, the naïve and honorable soldier, Don José, is seduced by the fiery and beautiful gypsy, Carmen, who works in a cigarette factory. She tosses him a flower, and he is instantly captivated, forgetting his childhood sweetheart, the gentle Micaëla. When Carmen is arrested for a fight, she persuades José to let her escape, a decision that costs him his rank. In Act II, Carmen and her friends are in a tavern, celebrating the victory of the bullfighter Escamillo. Don José, now released from prison, arrives to declare his love. Carmen demands he prove his love by deserting the army and joining her band of smugglers in the mountains. He refuses at first, but after a confrontation with his commanding officer, he has no choice but to flee with Carmen.

Act III takes place in the smugglers’ mountain hideout. Carmen has already grown tired of the possessive and jealous Don José. In a famous scene, she reads her fortune in the cards and sees only death for herself and her lover. Escamillo arrives, and he and José fight over Carmen. Micaëla then appears, pleading with José to return home to his dying mother. He agrees to go, but vows to return to Carmen. Act IV is set outside the bullring in Seville. Carmen, now the lover of the triumphant Escamillo, is confronted by a desperate and unhinged Don José. He begs her to come back to him, but she scornfully refuses, declaring that she was born free and will die free. As the crowd inside the arena cheers for Escamillo’s victory, the enraged José stabs Carmen to death.

The Characters

The genius of Carmen lies in its four perfectly drawn principal characters. Carmen is the ultimate femme fatale, a woman who lives by her own code of absolute freedom. She is a force of nature, mesmerizing and dangerous. Don José is her opposite, a simple man of honor and duty who becomes completely undone by his obsessive love for her, descending from a loyal soldier into a desperate outlaw and murderer. Escamillo, the toreador, is a figure of confident, charismatic masculinity, a public hero who is José’s natural rival. And Micaëla represents the world of innocence, purity, and simple domestic love that José abandons and can never reclaim.

The Music: A Spanish Postcard

Bizet, who never actually visited Spain, created a musical score of breathtaking and authentic-sounding Spanish color. He brilliantly evokes the atmosphere of Seville through the use of Spanish dance rhythms and melodic styles. The famous "Habanera" is a perfect example, its seductive, chromatic melody unfolding over the slinky, unchangeable rhythm of the dance. The "Seguidilla" in Act I is another brilliant Spanish dance, used by Carmen to complete her seduction of José. The preludes to the acts and the thrilling "Toreador Song" are filled with the brilliant, sun-drenched colors of Andalusia. This is not authentic Spanish folk music, but rather a masterpiece of musical exoticism, a French composer’s perfect imaginative vision of Spain.

An Unparalleled Legacy

After Bizet’s death, his friend Ernest Guiraud replaced the original spoken dialogue with sung recitatives, transforming the work into a grand opera, the form in which it is most often performed today. Within a few years of its disastrous premiere, Carmen began its inexorable conquest of the world’s stages. Composers, critics, and the public all came to recognize it for what it was: a revolutionary and perfect masterpiece. Its combination of unforgettable melodies, brilliant orchestration, and raw, realistic human drama changed the course of opera forever. It remains, by almost any measure, the most popular opera ever written.

You bet. Here is the story of Georges Bizet's Carmen.

Carmen is a tragic opera set in Seville, Spain, that tells a story of love, obsession, freedom, and jealousy. It follows the downfall of a naive soldier, Don José, who is seduced by the fiery and free-spirited gypsy, Carmen.

Carmen: A beautiful, fiercely independent gypsy who works in a cigarette factory. She lives by her own rules and values her freedom above all else. (Mezzo-soprano)

Don José: A corporal in the army, originally a simple and dutiful man from the country. His infatuation with Carmen becomes a destructive obsession. (Tenor)

Escamillo: A confident and glamorous bullfighter (Toreador) who becomes Don José's rival for Carmen's love. (Baritone)

Micaëla: A kind, gentle woman from Don José's hometown, who represents the simple, virtuous life he abandons. (Soprano)

Zuniga: Don José's commanding officer. (Bass)

Frasquita & Mercédès: Carmen's gypsy friends. (Soprano/Mezzo-soprano)

A Square in Seville

The scene is a busy square, with a cigarette factory on one side and a guardhouse on the other. Soldiers are milling about, watching the people pass. Micaëla, a young woman from the country, arrives looking for Corporal Don José. The soldiers tell her he'll be back with the changing of the guard, and she shyly leaves to avoid their flirtations.

The guard changes, and Don José arrives. His officer, Zuniga, teases him about the cigarette girls. The factory bell rings, and the men of the town gather to watch the women emerge for their break. The last to appear is Carmen, who immediately commands everyone's attention. She sings her famous "Habanera" ("L'amour est un oiseau rebelle"), a song about the untamable and rebellious nature of love. The men are all fascinated by her, except for Don José, who pays her no attention. Intrigued by his indifference, Carmen tosses a flower at him, which hits him in the chest. As the women go back to work, he picks up the flower, unsettled by her gesture.

Micaëla returns and gives Don José a letter (and a kiss) from his mother, who has written to say she hopes he will return home and marry Micaëla. The letter brings him back to his senses, and he resolves to follow his mother's wishes.

Suddenly, a fight erupts inside the factory. Carmen has slashed another woman with a knife. Zuniga orders Don José to arrest her. While Zuniga is writing the warrant, Carmen is left alone with Don José. She seduces him with another song (the "Seguidilla"), promising him a night of dancing and love at Lillas Pastia's tavern if he lets her go. Completely mesmerized, Don José agrees. As he leads her away, he "accidentally" allows her to escape. For this, Don José is arrested and demoted.

Lillas Pastia's Tavern

A month later, Carmen and her friends Frasquita and Mercédès are singing and dancing at a rowdy tavern frequented by gypsies and smugglers. The celebrated bullfighter Escamillo arrives to a hero's welcome, singing the famous "Toreador Song" ("Votre toast"). He is immediately captivated by Carmen, but she shows little interest.

After the tavern closes, the smugglers Dancaïre and Remendado try to enlist Carmen and her friends to help with a new smuggling run. Frasquita and Mercédès agree, but Carmen refuses—she is in love, she says, and is waiting for Don José, who was just released from prison.

Don José arrives, and Carmen is overjoyed to see him. She dances for him, but their reunion is cut short when a military bugle sounds, signaling him to return to the barracks. When he insists he must leave, Carmen flies into a rage, mocking his obedience and telling him he doesn't truly love her. To prove his love, Don José pulls out the flower she threw at him, which he kept while in prison ("La fleur que tu m'avais jetée"). Just as he is pouring his heart out, Zuniga, his officer, bursts in, also hoping for a tryst with Carmen. In a jealous rage, Don José defies his officer and draws his sword. The smugglers rush in and disarm Zuniga. Having assaulted his superior officer, Don José has no choice: his military career is over. He must now flee with Carmen and the smugglers.

A Smugglers' Hideout in the Mountains

Sometime later, the smugglers are in their mountain hideout. Carmen's love for Don José has already faded; his possessiveness and jealousy are suffocating her. The two quarrel bitterly, and she tells him he should go back to his mother.

While the smugglers sleep, Carmen, Frasquita, and Mercédès read their fortunes with a deck of cards. While her friends see futures of love and riches, Carmen's cards repeatedly foretell death—first for her, and then for Don José. She accepts her fate.

Micaëla arrives, having braved the dangerous journey to find Don José and save him. She hides when she hears a shot. Don José has fired at an intruder, who turns out to be Escamillo, the bullfighter, who has come to find Carmen. The two men, rivals for Carmen's love, begin a knife fight. The smugglers return just in time to stop them. Escamillo, undeterred, invites everyone, especially Carmen, to his next bullfight in Seville.

Micaëla is discovered. She desperately begs Don José to return with her, but he refuses to leave Carmen. Micaëla delivers her final, heartbreaking news: his mother is dying and has asked to see him. This news shatters Don José. He agrees to go, but as he leaves, he turns to Carmen and warns her: "We will meet again."

Outside the Bullring in Seville

The scene is a vibrant, festive crowd gathered outside the arena for the bullfight. Escamillo arrives in triumph, with a radiant Carmen on his arm. They express their love for each other, and Escamillo enters the ring.

As Carmen is about to follow, her friends warn her that Don José has been seen in the crowd, looking desperate. Carmen, in a fatalistic show of courage, says she is not afraid and will speak to him.

Don José confronts her, disheveled and frantic. He begs her to forget the past and start a new life with him. Carmen calmly and coldly refuses. She tells him she no longer loves him, that she was born free and will die free. "I am in love with Escamillo," she declares. From inside the arena, the crowd roars, cheering Escamillo's victory.

As Don José's pleading becomes more desperate, Carmen throws the ring he once gave her on the ground. Enraged, and hearing the cheers for his rival, Don José loses all control. "You will not go to him!" he shouts. As she tries to run into the arena, he pulls out a knife and stabs her.

The crowd pours out of the arena, led by a victorious Escamillo, only to find Don José standing over Carmen's lifeless body. He makes no attempt to flee, confessing in despair: "It is I who killed her. Ah, Carmen! My adored Carmen!"

Sheet Music International - Copyright 2026 all rights reserved